Chapter 33 - Loving Life - The End of the Memoir AFTER MARTHA

Despite the title of the last chapter, my grief over Martha is not entirely gone, nor is my mourning. But compared to how they used to dominate me, they are much more tolerable. I still think of Martha every day, and miss her. But I understand that the direction of my life doesn’t point to her anymore. It points to life.

The sun over Fifth Avenue in Manhattan in 2018

Chapter 32 - The End of Grief

After I sent my goodbye email to Nellie, I had dinner with Melinda at home and told her the whole story. She took it well and sympathetically. She had known about Nellie, but didn’t know how things had come to a head at our last dinner and about our breakup.

In 2019, I had a moment similar to that in the 1958 film Vertigo

Chapter 31 - Nellie

I was euphoric. I had a date with Nellie. Ostensibly, it was just a friendly dinner, but in my mind it was the opening for a love affair to begin.

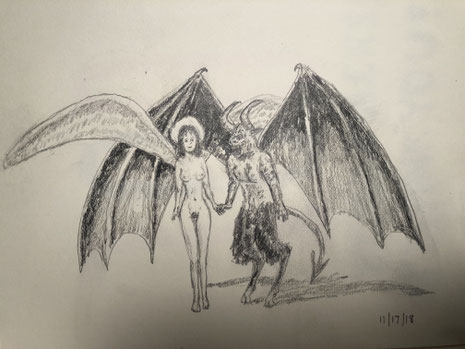

One of my sketches of Nellie, whom I loved in the winter of 2018-2019

Chapter 30 - Hypersexuality

Even before I got off the antipsychotic risperidone, there had been signs that my happiness at discovering beauty was starting to edge into mania. In the summer and fall, I had several irritable manic episodes where I got volcanically angry, exploding at one person or another with raised voice and a shaking left hand over trifling provocations. In October, I had an episode of hyperreligiosity that lasted all of ten days, during which I tried to live for God and eradicate my sins until I realized it was making me more irritable.

"The Marriage of Heaven and Hell," my sketch from fall 2018

Chapter 29 - Beauty

The bleakness I felt at the start of 2018 resulted, in part, from the problem I had had ever since Martha died: having no purpose in life without her.

"Melinda's Tops," the first painting I made after dedicating my life to beauty in 2018

Chapter 28 - Mad Pride

Ever since Martha’s death, I had tried to make sense of what she said on her last night: that she wanted to be mentally ill; that she considered illness better than health. I had told her then that I considered her to be using a different final vocabulary from mine.

Mad Pride marcher

Chapter 27 - How to Love Life

Lithium had always had the effect of deadening my spirituality, and it did so now. I kept going to Mass to escort Melinda, who needed my arm to lean on as we walked up the disabled ramp to Our Lady of Pompeii Church, a Dobbs Ferry church I joined in 2016. But if I didn’t need to take her, I wasn’t sure I would go.

New Hope, Pennsylvania, where I visited in 2017

Chapter 26 - Rolling the Dice

At the end of August 2016, I was convinced that I could still be in contact with Martha four years after her death. But as September began, I had an intimation that I was kidding myself.

Each day in fall 2016, I rolled a die to decide whether I would live or die

Chapter 25 - Cleave Land

From April to August 2016, I was manic. I didn’t know I was manic then but it made sense that I would be, because there was no lithium controlling my moods, just a little risperidone, and it wasn’t enough to cap the insistent climbing of euphoria. And the thing is, mania feels good, better than anything, and when you feel good you don’t think you’re sick.

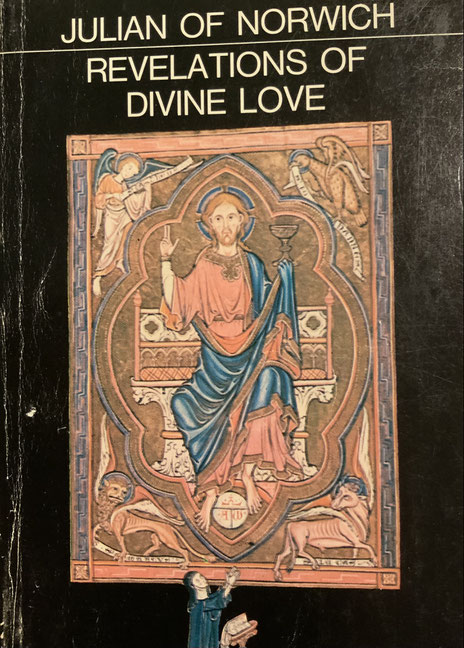

A book by Julian of Norwich that I found in Martha's room, 2016

Chapter 24 - Oasis

Ever since I lost my job at Magnificum, Melinda had feared for our economic future. If, as it appeared, I had developed a permanent mental disability, how would we pay the bills? Worse, how would we pay the hospital bills without health insurance?

Avril Lavigne's The Best Damn Thing, an album Martha and I both liked

Chapter 23 - Return to the Psych Ward

As early as May 2015, I noticed something was wrong with my memory. I couldn’t remember things I had written at work even a week earlier, and I was writing words that weren’t the ones I intended—again instead of ago, way for was.

The Shining (1980), a movie much on my mind at the psych ward

Chapter 22 - Scrounging

After my last official day at MediStory on September 13, 2013, I stuck around two weeks to fill in for the vacationing copy chief for hourly wages in the copy-editing department. People looked at me like a ghost then, as someone who no longer worked at the company but was somehow still eerily visible. After that, I stayed home, so as not to scare anyone.

The laptop from which I freelanced as an unemployed writer, 2013-2014

Chapter 20 - Psych Ward

From the movies, I expected the inmates of One South, the Phelps psychiatric ward, to be florid psychotics writhing in strait-jackets, but this was Westchester and they were more genteel. The twenty or so patients mostly had well-mannered complaints like depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and OCD.

"Screaming Father," drawn in the psych ward, 2013

Chapter 19 - The Call of Martha

On September 27, one month after Martha’s death, Melinda and I saw a bereavement counselor for the first time. A small, curly-haired woman named Betty, she worked in an office building in the Lord & Taylor parking lot in Scarsdale.

Hurricane Sandy knocks out power in New York shortly after Martha's death, October 2012

Chapter 18 - Settling into Mourning

On Labor Day, the Monday after Martha’s funeral, an Indian priest from our parish, Father Jim, came to our house to console us. We must have looked like we needed it, because he stayed two and a half hours. It was all part of settling into our new status of mourners of a lost child.

The Intrepid museum, around which I often moped about Martha on lunch hours at work

Chapter 17 - Aftermath

In this second part of the book, Martha is no longer alive. The story is no longer her story but mine: how I survived her death.

Martha's tombstone in Hastings-on-Hudson.

Chapter 16 - The Last Days of Martha

The summer of 2012 was Martha’s last summer. But before the end came another death: that of my mother.

Martha at eighteen with her bags packed for Columbia, on August 26, 2012, the night before she moved there

Chapter 15 - An Unstable Peace

In September 2011, Martha began her senior year of high school. It was the last academic year she would ever finish, the start of the last twelve months I would spend with her.

Martha at seventeen with her father in late 2011

Chapter 14 - Silver Hill

Despite the creative burst of her Logia writings, Martha began the new year of 2011 in deep depression. On January 28, she was on the verge of killing herself—I don’t know how. I know only that the next day in her journal, she wrote, “Yesterday I was almost brave enough to die; today I am hardly at that level. It terrifies me to think how close I came yesterday….I do not understand how anyone can want to live.”

Silver Hill Hospital, site of Martha's second psychiatric hospitalization in 2011

Chapter 13 - After the Attempt

After her

suicide attempt, we found

Martha at the

hospital, locked

up alone in

a small room with big

windows so she

could be observed continuously. She wore a

hospital gown and had nothing in her room but a bed, her

Bible, and a cup of ice water to relieve the burnt tissues of her throat.

Martha at sixteen in summer 2010, running the desk at our tag sale.

Chapter 12 - Crisis in Carlisle

Martha’s first year under psychiatric care led to the most dangerous crisis of her life until then. The crisis happened at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in the summer of 2010. But before then, she lived through a year of growing madness, seemingly intensified rather than subdued by her doctor’s ministrations.

Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Chapter 11 - Martha's Secret

As she started high school, Martha was a girl with a secret. She was passionately in love with a 300-year-old Russian prince, Aleksei—in fact, she had married him. She feared few people could understand the existence of this ghost husband, least of all her parents. So she kept us from knowing about him for as long as she could.

Martha at about fifteen in ninth grade, circa 2009, wearing black in mourning for Aleksei

Chapter 10 - Aleksei

At fourteen, Martha discovered the love of her life. He had been dead for three centuries, but to her he was still alive. He was a Russian prince named Aleksei. He accompanied her all the way to her death.

Russian tsarevich Aleksei Petrovich Romanov (1690-1718)

Chapter 9 - Deathwish

As Martha entered seventh grade, she became miserable, the beginning of a year of emotional problems. Looking back on her life later, she reflected that she had always had a melancholy temperament, but that it fully began to express itself on the first day of seventh grade, when she cried during her first orchestra class of the year.

Martha at fourteen in 2008

Chapter 8 - Rocky Times

In a diary entry on July 18, 2004, Martha at ten first showed signs that she was leading a secret life. “This diary is a front,” she wrote, “and all I can write in it is milestones, joy, and mock anger. Where can I express emotions?” I don’t know what emotions she meant because she didn’t write them down.

Martha at eleven in sixth grade, 2005

Chapter 7 - Bipolar Daddy

Until now, the focus of this book has been Martha. But for this chapter, I must turn the attention to me. As an indirect result of our family trip to Denver in 2003, I was diagnosed bipolar, and in the context of my diagnosis Martha’s insanity later emerged, the insanity that led to her death.

Fredric March as Mr. Hyde in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Paramount, 1932)

Chapter 6 - Juvenile Depression

Third grade was Martha’s first hard year of school. It wasn’t academically hard—academics was never hard for her. She almost always got Es, occasionally Gs, never anything less. We didn’t push her to excel; she pushed herself. But third grade was emotionally difficult. She had had an existential crisis during Christmas vacation in second grade, but third grade was rocky all the way through.

Martha at nine, getting off the school bus from third grade, 2003

Chapter 5 - Existential Crisis

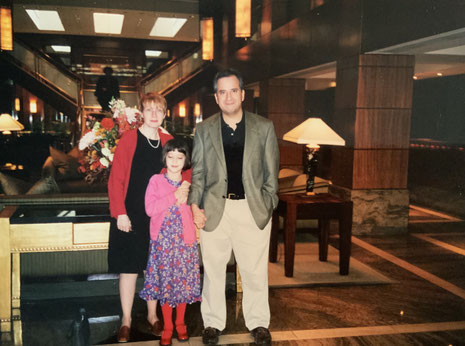

In September 1999, Martha started kindergarten in the Dobbs Ferry public school system. She would stay in that system for most of the rest of her life.

Martha at seven, with her parents, circa 2001

Chapter 4 - Preschool

In September 1997, Martha started preschool and the world changed. It changed in a way that was at first subtle but whose profundity would become clear over the years, like a crack that eventually becomes a chasm.

Martha at five, in 1999, at Community Nursery School

Chapter 3 - Only Child

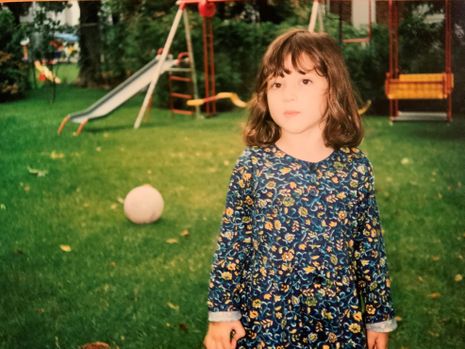

Martha now lived in the house and village where she would live until the night before she died.

Martha at three, in 1997, in her backyard in Dobbs Ferry

Chapter 2 - Martha's Littlest Finger

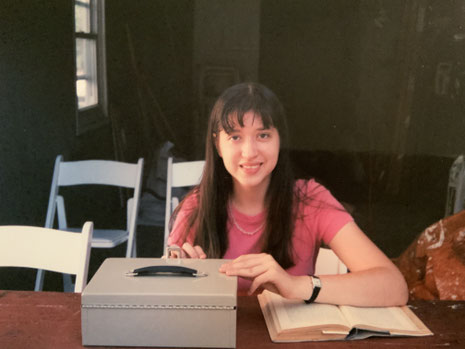

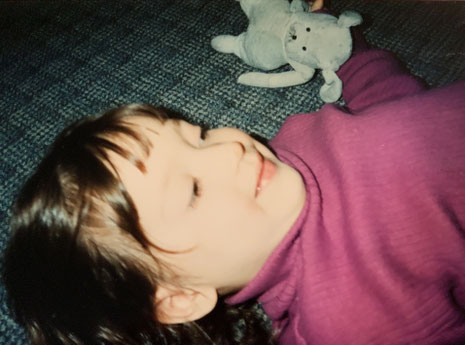

By the time Sad Dog became her chosen stuffed animal, Martha had developed a definite personality. Melinda and I called her “gentle and intense.”

Martha at two, with Sad Dog, in 1996

The Memoir AFTER MARTHA - Chapter 1 - The Happiest Day

My happiest day with Martha was the day I took her to Typhoon Lagoon. It almost made up for the day, years later, when she killed herself.

Martha at ten, with Piglet, in 2004, on her last visit to Disney World

Seven Years Later

Seven years ago today, Martha Corey-Ochoa jumped to her death from the fourteenth-story window of her Columbia dorm. In memory of her, and as a way of exorcising her ghost, I have just finished writing a memoir, After Martha.

Patriot of Madness

My daughter, Martha, died of being bipolar, but I do not think of bipolarity as a disease. I think of it as a gift, and I am proud of her for staying true to it to the end.

The Nobility of Suicide

Though I argued in my last post that a key question to ask a suicidal person is what he or she values more than life, I never thought to ask Martha this. So I do not know for sure what she would have said. But I suspect she might have said nobility.

See My Post at the Alliance of Hope

The Alliance of Hope for Suicide Loss Survivors is a wonderful website for people like me who have lost someone to suicide.

Advice to Parents with Mortal Children

Because my daughter, Martha Corey-Ochoa, died of suicide at eighteen, I am obviously the last person in the world to give advice on how to prevent suicide: I tried and I failed.

Martha's Secret

Many of Martha's friends and teachers knew about her mental illness, but because mental illness still carries a stigma, she had a dilemma when the time came to apply to colleges,

More about Martha

It's been a week since I announced this site to the world, and already it's had more than 300 visitors.

Why I Started This Site

Martha Corey-Ochoa, my only child, died at eighteen, and losing her caused me the greatest grief I have ever known.

Copyright 2023 Melinda Corey and George Ochoa. All rights reserved.