Even before I got off the antipsychotic risperidone, there had been signs that my happiness at discovering beauty was starting to edge into mania. In the summer and fall, I had several irritable manic episodes where I got volcanically angry, exploding at one person or another with raised voice and a shaking left hand over trifling provocations. In October, I had an episode of hyperreligiosity that lasted all of ten days, during which I tried to live for God and eradicate my sins until I realized it was making me more irritable.

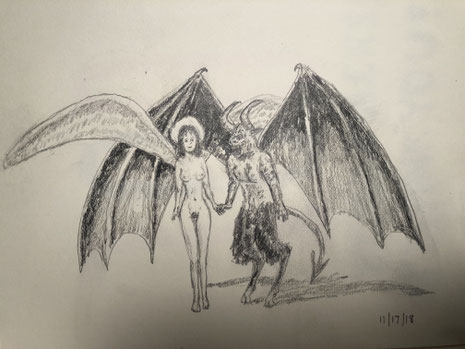

"The Marriage of Heaven and Hell," my sketch from fall 2018

I hid these episodes from my psychiatrist, or downplayed them, because I knew she wouldn’t take me off risperidone if she knew that I was already becoming manic. Risperidone was putting a cap on my incipient mania, and if the cap came off the mania might pour out in a full torrent.

Nevertheless, I was determined to get off another drug. With my psychiatrist’s consent (but without her knowing the whole story), I took my last dose of risperidone on Sunday, October 14. In short order, I had another two episodes of irritable mania. I became enraged at the president of the company when she reprimanded me over reminding her of a task she’d failed to do. I didn’t show her my rage directly, but I showed it to my boss, complaining tensely in his office, my left hand shaking. I carried the rage around all day. I couldn’t sleep that night for anger, and started looking for another job.

Then a coworker tried to change the date of a meeting I had set up, and that enraged me. I shouted at him; my left hand shook. I felt like I wanted to hit him. He complained to his boss, who spoke to me, and I let the date of the meeting be changed. Afterward, as usual, I regretted my outburst, felt I’d overreacted, worried that people would think I was crazy. I knew I was manic, knew the lack of risperidone was contributing. But I was determined to get off my meds. I wanted this not only for my sake, but, I felt, for Martha’s. She had been driven to her death by people trying to medicate her madness away. I had to vindicate her by showing that meds were not necessary—that a madperson could do better without them.

In the first two weeks of November, I calmed down. My irritability receded, and I hoped that I was right—that I could manage mania without the help of an antipsychotic. I was feeling better. Life seemed sweet again. Some of the pressure of hiding my bipolarity was lifted because on October 28 I went public about my diagnosis for the first time, in a blog post called “Patriot of Madness” on Martha’s website. I disclosed that I was bipolar as my daughter had been, and talked about how she had stayed true to her bipolarity to the end, like a patriot of madness. I said I was trying to stay true to it too by going off my meds. By that time, my boss and several coworkers followed me on social media, so they learned about my bipolarity too. It made me feel good to be open at last about my madness. I felt like I was making progress in vindicating Martha, while at the same time managing my bipolar symptoms so they didn’t derail me at work.

On Monday, November 12, a new employee started working at MedEquate. I glimpsed her on her first day, being trained at the big, silver front desk to work as office coordinator, a fancy term for receptionist. She had a wedge of curly red hair that extended left and right from her head, and big, soulful eyes with long, dark lashes. She was young and pretty, and I kept thinking about her after I got back to my desk.

Later that day a welcome email went around to all staff introducing the new girl as Nellie. The email said she had editorial experience and invited us to stop by and say hello. I usually paid no attention to such welcome emails, but I made an exception in this case. I stopped by and introduced myself, and asked about her editorial experience, which amounted to working on her college paper and doing some freelancing. I let her know I was director of communications, and she said she would be interested in working in communications. The whole time we talked I couldn’t take my eyes off her. Her big eyes blinked a lot, and she had a birdlike way of fidgeting that made me want to watch her closely to track where she shifted next.

That week I stopped by her desk several times, the way I never had with any other receptionists. I didn’t even have excuses to stop by; I just wanted to look at her and chat. I asked what she was reading—I figured a woman like her would be reading something, and indeed she was, a recent novel by Jesmyn Ward, Sing, Unburied, Sing. I found out where she lived (Spanish Harlem), where she grew up (Northampton, Massachusetts), where she went to college (U Mass Amherst). I found out she had several tattoos on her arms. On her left arm were roses, a cat, a semicolon. On her right arm was the sentence Feel this moment.

I don’t know if it was because of Nellie, or if my interest in Nellie was only a symptom, but that same week I became exceedingly interested in sex. All week my groin felt hot, as if a pilot light that had been off had just gotten turned on. Melinda and I had sex, twice, for the first time in months. I had lunch with Esther and was more attracted to her than usual, enough to make me fantasize about having an affair with her. I looked at pictures of scantily clad women on Instagram and Pinterest, and drew and posted female nudes, including, on my birthday, a sketch of a naked female angel marrying a lascivious demon that I called “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.” I thought about seven women I’d loved in the past but been unable to attain and keep—among them Mary Ann, Sarah, and Stevie—and wrote a personal essay about them called “Seven Women I Never Slept With.” I wondered if there would be an eighth of these unattainables, as I called them. Maybe Esther, if I suffered more for her; suffering for a woman is vital to her unattainability. Maybe Nellie, if I got to know her better.

When these feelings continued into a second week of flirting with Nellie and Esther and writing and drawing sexually charged works, it was clear that I had hypersexuality, the excessive interest in sex that is a symptom of mania. It seemed evident that my going off risperidone had led me to this manic pass, and that, if I wanted to be honest with my psychiatrist, I should let her know. But I knew that if I told her she would try to put a stop to it, probably by putting me back on risperidone, and I didn’t want to stop it. I liked being hypersexual. Women were beautiful and exciting and I wanted more of them, not less. I was the dedicated servant of beauty, and right now I served her by focusing on the most beautiful of all creatures, women. My mood was high, my creativity booming. Besides, no one was being harmed. My wife was pleased with our renewed sex life, and despite my attentions to other women, I had no serious intention of having an affair.

Vaguely, my hypersexuality was tied to my continuing efforts to vindicate Martha. On Facebook the night before Thanksgiving, I posted a provocative paragraph in which I said that when sane, I regarded life as a friend to be enjoyed, but when insane, I regarded life as an enemy to be conquered. From the latter perspective, suicide was the conquest of that enemy, and Martha was a hero for her victory.

Shortly after I posted this, the doorbell rang. Melinda answered it and found two policemen. They called me downstairs and asked about the Facebook post. Someone apparently had reported it and was concerned that I was suicidal. I was extremely nervous, because I knew that if I sounded suicidal the police had the power to lock me up in a mental hospital, and I had no desire ever to go to a mental hospital again. So I carefully explained that I was not suicidal or even depressed, that I had just been posting a philosophical thought. The cops looked at me suspiciously but eventually believed me and left.

After the policemen departed, I realized that I was becoming a danger to myself—not because I might commit suicide, but because my mania was causing me to act erratically, with poor judgment about how others might interpret my actions. I had thought my Facebook post was harmless, but someone—probably Facebook itself, based on its algorithms for detecting suicide threats—had considered me a dangerous lunatic. For all I knew, people at work were similarly becoming suspicious because of my flirtatious behavior, randy social media drawings, and open espousal of bipolarity. I might have thought of toning down my behavior, or seeking medication. But I didn’t. For Martha’s sake, I was dedicated to being a patriot of madness, just as she had been. I wasn’t going to let a couple of cops scare me into censoring my ideas, art, or behavior. Martha had considered 1984 a metaphor for the efforts of sane society to suppress madness and crack down on thoughtcrime, and I felt the same way. Like her, I was now an ardent foe of Big Brother.

So I continued feeling hypersexual and euphoric and being hypercreative. I kept flirting with Esther, talking about how I wanted to stop by her office every day from now on and have lunch with her once a month. She agreed, and we scheduled our next lunch for December. I got Nellie to send me writing samples, and I praised them profusely—maybe a little more than they merited—and talked to my boss about getting her transferred to our department. I learned that Nellie had done volunteer work answering calls for a mental health hotline, and we talked about mental illness and suicide, and I told her about Martha. Like most people, she was shocked to find out that I had a daughter who’d died of suicide. In a subterranean way, I felt glad for having that story to tell Nellie, to make her more interested in me.

Sleep became difficult because of the thoughts and writings racing through my mind, the heat in my crotch, the fantasies of love affairs. At first I only fantasized about Esther, but she was out one day, giving me less time to interact with her and more time to stop by Nellie’s desk, which shifted the emotional balance. After that I had torrid fantasies of sex with Nellie, spent more time watching her skinny body flit about the office in her little black skirts and dark hose. One day she asked me if I wanted her to keep delivering my junk mail, and I said, “Yes! I get to see you!”

On Monday, December 1, I took Nellie out to lunch at a Brazilian restaurant. I learned that she too was bipolar—type 2—confirming that I have an unerring eye for detecting and being attracted to women who are bipolar. She let me study her tattoos, and a set of faint white marks on her left arm where she used to self-harm. She talked about the suicidal feelings she had had, and how it had led her to tattoo the semicolon on her arm, as a symbol of wanting to continue with life (depression as a semicolon interrupting life, not ending it with a final period). I learned about her boyfriend of six months, heard more about her fiction writing, found out she was half-Jewish but not observant.

On our way back to work, we passed a construction site, and like a little girl she peered excitedly through a porthole in the green wall at the machines and dirt, and flashed an exuberant, toothy smile. I loved how young she was. At twenty-six, she was almost the age that Martha would have been (twenty-four) had she lived. She didn’t look like Martha, but she reminded me of Martha—the soulfulness in her eyes, the sadness (I have always loved sadness in a woman’s eyes); the bipolarity; the history of suicidality; the literariness. She reminded me of the young Melinda too—with her milky skin, round face, and red hair—but even more of Martha.

Martha was on my mind because I was thinking again of writing my book about her, Supernova Girl. That weekend, I had started reading her diaries systematically, beginning from when she met Aleksei in 2008. It seemed to me that Martha’s story was essentially one of forbidden love, like Romeo & Juliet, with Martha as Juliet, Aleksei as Romeo, and Melinda and me as the uncomprehending parents standing in their way. We tried to tear them apart with psychiatry and drugs, and succeeded only in bringing about the death of our daughter. I would tell the story novelistically, based on her diaries.

This new approach to Supernova Girl marked how far I had come in villainizing psychiatry. The way I saw it now, psychiatric treatment, in particular medication, had driven Martha to her death. Since I was the one who had demanded that Martha undergo psychiatric treatment, I was primarily responsible. I was her murderer. Now I was dedicating my life to correcting my error, guided by her voice as preserved in her diaries. I was like Richard Burton as the Roman centurion in The Robe, who crucified Christ and then was converted to Christianity. My own forsaking of psychotropic drugs was the first step along my path of discipleship. You can always count on a manic person for a grandiose story.

As a down payment on the story, that Thursday an essay of mine was published on Mad in America, an antipsychiatry website I had discovered during my Mad Pride-related research. Called “Why My Daughter Died and I Lived,” the essay compared Martha and me as two people who had been suicidal in our teens, and noted that the difference between us was that she was treated with psychotropic drugs and I wasn’t. Psychiatric treatment, I concluded, had not saved her and might have hastened her death. I shared the essay with friends on social media and several people at work, including Esther and Nellie. It gave me pleasure to know that two women I was attracted to were seeing me published and reading my work.

The next day Nellie got fired. Neither of us saw it coming. It was the end of her fourth week at MedEquate, and I thought she would be there a long time. But she appeared in my doorway that morning telling me she’d just been let go. She was being escorted out, but her escort, waiting for her at the front desk, had allowed her to come say goodbye to me. She looked forlorn and bewildered, and, strangely, the sight of her distress made me even hotter for her. I am not a monster; of course I cared about her. But inside I felt deep satisfaction that she had wanted to say goodbye to me.

I closed the door and sat her down. With my office-mate—the female writer whom I supervised—I listened to her story and tried to comfort her. The senior management at MedEquate had felt Nellie was making too many mistakes. Nellie didn’t know what she was going to do now. She looked stunned and scared.

I did my best to encourage her. I told her this was the luckiest break she had ever gotten. She was going to get a much better job and have a great literary career. “You’re more talented than you know,” I said. I meant this—I thought Nellie was talented, and thought she undervalued herself—but I also said it because I desired her and wanted her to desire me too. As I spoke, I looked deep into her big, soulful eyes, which I had learned that week were hazel, just like those of Sarah and certain other women I had loved. And I asked for her email address and phone number. She gave them to me. I hugged her, the first time our bodies had ever touched, and kissed her cheek. And she walked out.

She walked out, but from then on she was all I thought about. Somehow her departure from MedEquate ignited my passion for her, as if now I had permission to court her as I couldn’t when she worked there. Later that morning I sent her an email with the subject line “let me help,” in which I offered her help in finding another job and told her, “I’ve never met anyone quite like you.” I asked her to dinner next week. After an hour I became concerned that she wasn’t emailing me back, so I went down to the lobby for privacy and called her on my cell. She was, it turned out, just in the process of emailing me back to say yes. We set the date for Tuesday.

Copyright 2020 George Ochoa.

Write a comment