Ever since Martha’s death, I had tried to make sense of what she said on her last night: that she wanted to be mentally ill; that she considered illness better than health. I had told her then that I considered her to be using a different final vocabulary from mine.

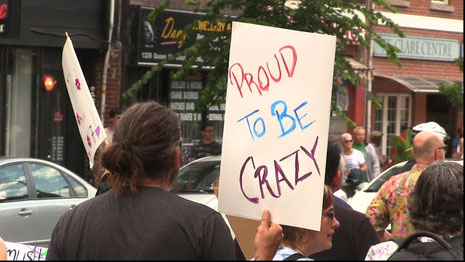

Mad Pride marcher

Since her death, I had wondered if I could translate from her final vocabulary to mine, if I could see how mental illness was better than mental health. Now, in the last days of August 2017, five years after her death, it finally became clear.

Right now, virtually all the words in our society’s vocabulary for people like Martha and me are either clinical or pejorative. On the clinical side are mentally ill, sick, psychotic, insane, bipolar, schizophrenic, depressed; on the pejorative side are mad, crazy, nuts, deranged, lunatic, loon, wacko, psycho. The clinical terms, though more polite, are themselves pejorative because illness is something bad and unwanted. So there is no way to describe people like Martha and me in a positive or even neutral way.

I tried to imagine what such a word would be and came up with heteromental, people with different kinds of minds, in contrast to the homomental, people with all the same kind of minds. Being different is not necessarily bad, and might even be good, because diversity in a population increases the odds of traits being available that are adaptive to changing conditions. Since a heteromental person is not, by virtue of that name, presumed to be sick, she doesn’t necessarily require treatment—only if her mentality causes dysfunction or suffering. Her heteromentality is a gift, an intrinsic part of her personality, part of what makes her unique. Without the heteromental, the world would be poorer, because it would lack the unique capacities and points of view that the heteromental offer.

When Martha said she preferred mental illness to mental health, she perhaps meant that she preferred heteromentality to homomentality. Or she might have meant something even stronger—that there was a greatness or nobility to heteromentality that made it superior to the alternative. There was also a cost, and she willingly paid the full price.

###

My idea of heteromentality was the first breakthrough I had had in understanding not only Martha’s last words but who Martha was and what the meaning of her life was. But I didn’t particularly like the term. I have a distaste for long Greco-Latin words when short Anglo-Saxon words like ill or mad are available. Besides, difference (the root meaning of hetero) was too bland a concept to cover Martha’s sense of her condition—the greatness, the nobility, the tragedy.

I wrote a brief essay about heteromentality, in which I tried to explain the term, but it seemed inadequate to the ideas I was forming. I realized I needed to do research to find out what other writers had said or thought about the issues. I vaguely recalled that Foucault had written on the subject, so I picked up his Madness & Civilization. From that book, I got a historical view of how society has exerted control over the insane through a series of mechanisms that in the past included iron bars and chains and whose current form is modern psychiatry. I also got the sense that something essential is lost when a lunatic gets treated medically. It’s not like getting cured of an infection, which attacks from without, or a cancer, which attacks from within but is not the person. My insanity is me. To “cure” me of insanity is to rid me of myself, or part of myself—maybe the core part.

Back in 2003, when I sought treatment for depression, I had signed on to the medical model of madness, which regards madness as an illness to be treated. While under the influence of that model, I had made Martha submit to it too. But after many years of treatment, I wasn’t sure that I was any happier or better off than when I started. My mood swings were a little less dramatic, enough so I could hold down a full-time job, and in that sense I was more functional. That made me a better tool for industrial capitalism. But did it make me happier? And was my functionality being improved for my sake, or for the sake of my bosses—as if I were a photocopier of theirs getting a drum replaced?

And what about Martha? After three years of psychiatry, she had killed herself. Maybe she would have done so anyway, but at the least it wasn’t obvious that psychiatry had helped her or extended her life. Maybe psychiatry had shortened it. I knew she hated being treated for mental illness. She had said in her paper on Hamlet, “Rather than trying to suppress and treat insanity, society should find a way to appreciate and apply the insights gleaned from people who experience insanity.”

She hated the pressure to be sane. Maybe it was her insanity that killed her, but possibly her insanity would not have done so except in response to the pressure to be sane.

I began to think of writing a book about my developing views, to be called Wildwisdom, a title that was my second attempt, after heteromentality, for a better word for mental illness. One day as I avoided work by Googling these issues, I came across an international movement called Mad Pride. This is a movement of mental patients who no longer believe psychiatry, particularly psychiatric medication, is the answer to their problems. They know there is something different about them and that it causes them turmoil, but they resist calling it an illness. They prefer to call it by the old terms madness or craziness, names formerly pejorative but embraced by them now as badges of honor, marks of pride. In this way, they defang the old insults, reclaiming them with a new, positive meaning, much as gay and lesbian people have done with queer.

I don’t think Martha ever heard of Mad Pride, but she might have approved if she had. In her diaries, she often calls herself mad or crazy, with no hint that she thinks that’s a bad thing, even though she knows other people think it is. She hated being called mentally ill, hated her doctors’ and parents’ insistence that her love for Aleksei was nothing but a sign of sickness. Her love for Aleksei was the central meaning of her life, and she was proud of it.

Similarly, people in Mad Pride who have delusions and hallucinations think of them as personally significant in some way, not merely symptoms. They may think that their alternative way of perceiving reality opens the door for them to some higher or nobler way of being. In the same way, the creativity, intelligence, and sensitivity associated with bipolar disorder make bipolar people unusually valuable. Madness, in the Mad Pride view, is at least as good as sanity, and in some ways better.

It is not that the proud mad don’t recognize they have problems. They know their problems all too well. Depression and anxiety are excruciating. Not being able to hold a job can make you destitute. But the proud mad think there may be better ways to improve their condition than that of the conventional medical model—different forms of seeking counsel or redirecting their spirits; alternative ways of making a living. And if the problem is one of not being suited to society, they don’t entirely see why they are the ones who have to adjust rather than society. Thus Mad Pride, potentially, is politically radical. It critiques society, asking if it isn’t society that has to change how it handles the mad rather than the mad who have to change to fit society.

As soon as I read about Mad Pride, I liked it. It articulated what I had been trying to say with my talk of heteromentality or wildwisdom, but without recourse to such cumbersome locutions. I much preferred calling myself mad than heteromental or wildwise. Most movingly, this view of madness was close to what Martha had been trying to tell me with her last words about preferring mental illness to mental health. By declaring myself mad and proud, I was reaching across the grave to my daughter, who had been mad and proud before me and had tried to show me the way. She died to show me, by staying true to her madness to the end. In some way, I was even proud of Martha for having killed herself.

If Mad Pride were an organization, I would have signed up right then. But the mad, apparently, were at that time too disorganized to construct a large-scale membership association of the kind I wanted, and I was too much of a reclusive, individualist writer to found one myself. So I had to content myself with the kind of action a writer can take: writing a book. I would write a book about my evolving view of madness, and would show how it connected to Martha’s life and death.

To write books one has to read books, and I read several. It turned out there is a whole literature of antipsychiatry—the concept, closely related to Mad Pride, that psychiatry is an inadequate, problematic, or even disastrous approach to madness. One of the classics in that literature is The Myth of Mental Illness by Thomas Szasz, which profoundly influenced me by arguing for the speciousness of the concept of mental illness. The idea of mental illness, Szasz argues, arose by analogy to physical illness. But whereas physical illness is a bodily impairment, often diagnosed with the aid of biological tests, mental “illnesses” by definition are not bodily (if one is shown to be bodily, it ceases to be classified as mental) and there are no biological tests for them. With Szasz, I agreed that this is because they are not illnesses at all—just sets of thoughts and behaviors that violate social norms. Unlike Szasz, who thought there was no biological component to these thoughts and behaviors, that it was just a game people played, I did think there was a biological side—that I had a genetic susceptibility to playing the bipolar game, and had passed it onto Martha. But even though bipolarity, in my view, was in part genetic, it was not a disorder in need of treatment but a set of traits in need of tolerance and, in some ways, celebration.

Then I read R.D. Laing’s The Divided Self, and gained insight into myself by how he described the divided selves of schizophrenics. I was divided, I realized, into at least five selves, four inner and one outer. The inner selves were a saint (site of my religious and moral life), a genius (site of my artistic and philosophical life), a beast (site of my sexual and animal life), and a lost soul (site of my depressive and suicidal life). The outer self was a normal-seeming wrapper that interacted with the outside world and tried to keep the inner selves integrated and under control. The story of my life was one of pressure and competition among the different selves, particularly between the outer self, who wanted to appear sane, and the inner selves, who didn’t care if they appeared insane. Martha had had her own contest between her sane and insane selves, whose taxonomy she had not lived long enough to make out fully.

I talked with Melinda about my emerging views on madness and how they related to Martha’s life and death, and she observed, “I don’t think I mourn enough for Martha.”

“I think I mourn for her more than you do,” I said.

“Yes,” she said.

“When you lost her,” I said, “you lost a child. When I lost her, I lost a child and a soulmate.”

This, perhaps, was the crux of my research into madness. Martha had been mad like me, and that had made us soulmates, and I was trying to revive her by reviving the connection between us. Once again, I was denying Martha’s death by trying to resurrect her. Even now, five years after her death, I still had periodic moments when I felt the raw pain of her death, like looking into a deep pit you had forgotten was at your feet. I still craved Martha’s return.

I was learning to see madness as a point of pride, one that I shared with my daughter, one for which she died as the martyred saints had died for Christ. Just as the stories of the saints encourage Christians to go and do likewise, Martha’s story encouraged me to imitate her. But I would not imitate her by killing myself. Rather, I would imitate her by being true to my madness in my own way.

One way I could do that was to stop suppressing it with medication. If Szasz was right in saying that there is no mental illness, then I had no need of medicine to treat it. I could prove his point by going off my meds, as many in the Mad Pride movement had already done.

This idea scared me. I had gone on meds for a reason—to fight severe depression. Only the year before, in fall 2016, while off lithium I got into a black depression that almost killed me until I went back on lithium. And there were other dangers than depression—the bizarre symptoms of mania; the chance that I would become so unbalanced that I would be unable to hold a job.

Yet the meds were ineffective in many ways. I didn’t feel that I had been any happier in the fourteen years that I’d been medicated than in all my unmedicated years before. And something had been lost to the meds—I had been blunted emotionally and spiritually, suffered a loss of creativity. I felt I owed it to Martha at least to make the experiment of recovering my unmedicated self.

I had a feeling Dr. Kalinovka would resist taking me off my meds. Psychiatrists tend to think that meds are the only thing keeping their patients sane. If the patient is doing well, don’t endanger the good state by taking away the meds; and if the patient is not doing well, add more meds. For a while, I resisted talking with her about it for fear of getting into an argument and being put in my place as a patient. The feeling of being trapped made me depressed, and for the first two months of 2018 the world seemed particularly bleak.

Finally, in March, I told my doctor I wanted to get off my psychotropic drugs, which at that time numbered four: lithium, Klonopin, Effexor, and risperidone. As I expected, she was hesitant, but not as dogmatically opposed as I had feared. She said she was willing to reduce my dosages and even eliminate some drugs, except for one: lithium. She said that as a bipolar person I needed that one to keep my mood stabilized. If I ever wanted to get off that, I would have to do it without her assistance.

I accepted her terms, thinking that if, with her help, I gradually tapered off the other drugs and found I was doing well, I could always go off lithium on my own. So we started the experiment by reducing my dosages of Klonopin and Effexor.

By that time, there had been another change in my life. I had discovered a new purpose in life: beauty.

Copyright 2020 George Ochoa.

Write a comment