Ever since I lost my job at Magnificum, Melinda had feared for our economic future. If, as it appeared, I had developed a permanent mental disability, how would we pay the bills? Worse, how would we pay the hospital bills without health insurance?

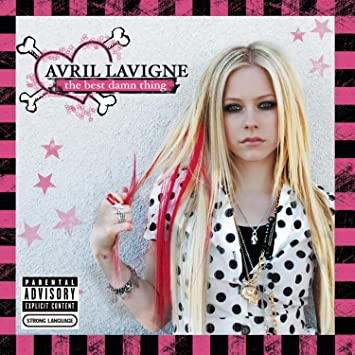

Avril Lavigne's The Best Damn Thing, an album Martha and I both liked

As it turned out, she did not need to worry about that last point. Chuck, the boss who had berated me on my last day at Magnificum for my terrible work, became much more human once Melinda called and told him I was sick in the hospital. He insisted on leaving me on the company’s health plan free of charge until I was better. It was the nicest thing an ex-boss had ever done for me. As for paying our other bills, my father was worried about my health too, and he chipped in a large sum every month while I was sick.

Still, in the long run, I would need a job for us to remain solvent. And in that department, it appeared someone else was looking out for me too, by which I mean God. The very evening I came home from the hospital, the phone rang. It was somebody from a company I had never heard of called MedEquate, saying they wanted to do a phone interview with me for a staff writer job. I was still weak and confused from my illness, and had no idea how these MedEquate people had gotten my name. But I needed the gig, so I set up an interview for that Friday afternoon.

In time, I would unearth computer records from two months earlier indicating that MedEquate had posted the job opening on Monster.com and that I had sent them a resume in response. I was so foggy at the time that I didn’t even remember doing it. But somehow I had managed to apply and they had responded—and had waited to respond until the very day I was released from the hospital. Had they responded any time earlier, I would have been too sick and crazy to continue the job application process.

Since Martha’s death, I had had trouble believing that God cared enough about me to do anything nice for me. For the most part, I didn’t even bother praying for material things anymore. But he appeared to have done one nice thing for me without my praying.

I was still weak and shaky from my months of illness, complicated by a persistent anemia I had picked up. My mood was shaky too; without lithium to stabilize it, I shifted easily from hypomania (light mania) to neutrality to low spirits. I was on three other drugs—risperidone (an antipsychotic), Effexor (an antidepressant), and Klonopin (an anti-anxiety drug)—but lithium had been my main mood stabilizer for years. Still, I managed to drive myself to St. Vincent’s Hospital in Harrison, New York, every day for two weeks for another partial hospitalization. There I got refresher courses in CBT, DBT, and mindfulness training that acted as a sort of booster shot for all the various cognitive strategies I had learned over the years for dealing with my bipolar disorder—what I called “Jedi mind tricks.” I also dabbled in art therapy and got to know my fellow crazy people. They were a scrappier lot than at my last partial hospitalization, with more chemical addictions and prison terms.

My mood was generally pretty good, but I hadn’t lost the dislike of life that had led me to attempt suicide by starvation. On my birthday, November 17, when I turned fifty-five, I thought about the child I had lost and told Melinda, “Martha did the right thing.” Martha had had the courage to check out of life when she had the chance. It seemed to me that she hadn’t rejected the rational; she had sought an integration of the mad, the holy, and the rational, with the mad on top. I also thought that on her last night, when she told me she preferred mental illness to health, she had been saying, “Give me the freedom to die.” And by the way I answered, in my talk about our having different final vocabularies, I had told her, “I give you that freedom. But might not knowing that I give you that freedom, that I understand you that far, be enough reason to stay alive?” She answered, “No.” And that was how she died—free, released by me.

I credited her with courage for taking that freedom. But that night of my birthday, after I took out the garbage, I looked up at the stars, crisp and clear in the wintry air, my breath congealing for the first time that season, and I said to myself, “Stay alive.” It was what I had told the young suicidal man in One South. Stay alive. Finish the race.

I realized that in the three years since Martha died, I had died too. And I was only slowly coming back to life.

Even while I was returning to life, I began to have dreams of Martha coming back to life too. In my dreams she was often a child again, somehow resurrected from the dead. Death had damaged her, left her mind impaired, her speech strange. Her cheek was tinted green with mold. But I was glad to have her back, excited to have a second chance at raising her. This time, I always thought, she would not commit suicide; this time I would protect her. Then the alarm clock rang and I woke up, and I realized it had been a dream. I grieved to learn all over again that Martha was still dead.

###

While at St. Vincent’s, I did a phone interview with the COO of MedEquate from my car in the parking lot. When he asked me how I left my last job, I didn’t mention that I had gotten fired but said I had left for “health reasons”—which was sort of true, since I had gotten fired primarily for poor performance due to my undiagnosed lithium toxicity. Had the COO asked me what the health reasons were, I would have told him frankly about my bipolar disorder and lithium toxicity, but he didn’t ask. Favorably impressed with the rest of the phone interview, he decided it was worth having me come in for a day of in-person interviews. And that posed a minor problem.

The problem was that none of my suits fit anymore. I had lost thirty pounds and they were all much too big. The live interview was in just a few days, so I had to rush down to Brooks Brothers at the Westchester Mall and buy an emergency skinny suit tailored to my new physique. Being Brooks Brothers, they did the alterations in just a day. I also bought a new shirt, tie, and briefcase for the occasion.

Suitably bedecked, I went into MedEquate, met with a series of executives, and nailed the job. They made me an offer for a higher salary than I’d been making at Magnificum. I postponed the start date until after I finished partial hospitalization and some freelance assignments, so I didn’t start until Monday, December 7. It was one of the easiest hiring processes I’d ever been through. As for the suit, that was the last time I wore it. I quickly gained back the weight I lost, and the suit never fit again. But it had done its work on the one day of its wearing.

###

After all I’d been through since Martha’s death, starting work at MedEquate as a senior writer was like landing in an oasis following a hard voyage in a desert. The commute was easy—the company was located near Grand Central, where my train from Dobbs Ferry came in. The digs were swank, with an off-white and lime-green color scheme and a conference table the size of a battleship. For the first time since I left my home office, I had an office with a door rather than a mere desk or cubicle, though I had to share the office with a coworker. The work was hard, and I pulled some late nights, but it was more rewarding than medical education, because MedEquate, a healthcare data firm, was a nonprofit with at least a kind of social mission.

What’s more, they appreciated me there. From the beginning, many people, including some high up in the company, remarked on the good job I was doing. Some months into my tenure the president of the company, a woman about Melinda’s age, touched my shoulder and said, “We love you, George.”

My office mate was Ted, a short, round man with long hair and a beard, like an aging, but neat, hippie. He wasn’t my boss, but as director of communications and editorial services, he edited everything I wrote. I have never liked being edited, but I accept editing readily as a mark of my professionalism, so he and I got on pretty well. I told him about the loss of my daughter, a story that always stuns people and leaves them unsure of how to respond. It’s uncomfortable enough that I usually don’t bring Martha up unless the conversation turns to children, especially whether I have children. But if the conversation does turn that way, I never hide her having existed, because that would suggest I’m ashamed of her, which I’m not.

Even though I told Ted about Martha, I didn’t tell him about my bipolar disorder. I had lost two jobs, at MediStory and Magnificum, when the bosses learned about my mental illness or its symptoms, and I was determined not to let MedEquate be the third. No one at MedEquate was going to learn I was bipolar and I would not let my symptoms disrupt my work.

I still felt sad every day about Martha’s death, but I was trying to recover parts of my old life. One way I tried to do that was through music. I remembered how the song “Hey There, Delilah” had struck me in One South, and I realized that since Martha’s death I hadn’t played any of the CDs in my collection. I used to play them often, but Martha’s death seemed to have knocked music out of the house. Back in 2007, when Martha was thirteen, I had gone through a period of listening to current pop music that had started with Avril Lavigne’s song “Girlfriend.” On January 3, 2016, I dug out the CD with that song, The Best Damn Thing. Lying on the playroom sofa listening to it again was like finding a treasured toy from my childhood I had forgotten I once owned. It wasn’t just that I liked the album; it was that Martha and I had often listened to it together, and I had introduced her to her own taste in pop music with that album. Listening to Lavigne singing those songs was like resurrecting Martha. The experience was so emotional that I didn’t immediately repeat it. It would be a long time before music would again become a regular part of my life.

Another part of my past got a bigger resurrection: writing short stories. I hadn’t completed a short story since before Martha died, but, from January to April, I wrote ten. It was one of my most fertile bursts of creativity. A couple of stories were about Martha, but most were about other things—episodes from my past, made-up scenarios. I tried getting them published in literary journals, but had no success for a long time. (Eventually one got published, “Alicia Brings Home Her Shrink,” based on my relationship with my sister, but not for two years, until 2018.) It didn’t matter much. The joy was in creating them. For months, I lived and breathed fiction, thinking of scenes and plots while I was supposed to be working, struggling to shut down my ideas at night long enough to get to sleep.

I wondered if I was hypomanic, and I probably was, but I played down that possibility when talking to my psychiatrist. It was a new psychiatrist, a Russian woman named Dr. Kalinovka. I had fired Dr. Sanders because he had so overloaded me with drugs that I had landed in the hospital with lithium toxicity. Dr. Kalinovka was willing to keep me on a lighter regimen of drugs that didn’t include lithium. But she was suspicious about my burst of creativity and wondered if I was too lightly medicated, whether I should go back on lithium. At that point, having almost died from lithium, I was trying to avoid it, and she let me stay off it for the present.

One sign that I wasn’t manic was that I wasn’t chasing women—not very energetically, anyway. There were a couple of attractive young women at MedEquate, and one of them, Esther, was sufficiently interesting that I asked her to lunch. She was a small, slim, black-haired woman of thirty-three, a highly religious Iraqi Jew who left work early every Friday to spend the sabbath with her parents in Queens. She was well-educated and literary, a writer, and over the next few years she became my best friend at MedEquate. Over many lunches—always at kosher restaurants, to accommodate her dietary requirements—she confided in me about her love life as a single woman and we talked about books and many things. But I didn’t fall in love with Esther the way I had with Sarah and Stevie. I thought she was pretty, but I was mostly able to keep myself from fantasizing about where our relationship could lead.

My mood at MedEquate stayed serene until the early spring, when I had a bout of depression and anxiety. For days, I felt a kind of mental nausea or revulsion about working—a version of my usual distaste for the pointlessness of jobs—and mimed cutting my throat and stabbing my heart. Dr. Kalinovka wanted to put me back on lithium, but I resisted, and she adjusted other meds instead. My mood got better but remained rocky.

Around that time fell Martha’s twenty-second birthday. By then, had she lived, she would have been preparing to graduate from college. Melinda and I went to a friend’s birthday party at that time, a party whose guests included parents of Martha’s former classmates. We sat with these parents at dinner in a dark Italian restaurant hearing about the wonderful things their children were doing—one of them was going to open a store; another had won a prestigious Princeton-in-Asia fellowship to be a journalist in Seoul. It infuriated me to hear about the glorious accomplishments of other people’s children while no one even mentioned Martha. It was as if she had never existed. I deliberately stuck in her name a couple of times, making people look guilty and fill their mouths with compliments about her. But I understood. People want to share news about their children. There was no news about Martha; there never would be. Every accomplishment of hers was forever in the past.

Part of the awkwardness is that there is no word for people who have lost a child. If you lose a spouse, you’re a widow or widower; lose a parent and you’re an orphan. But lose a child and you’re unspeakable. Maybe if a word were invented for people like me, deprogenite, say (for being stripped of one’s progeny), others would know how to include me in social situations.

Copyright 2020 George Ochoa.

Write a comment