Even though I had been discharged from the hospital, I was not considered well enough to go straight back into normal life. Instead the doctors sent me into what was called a partial hospitalization program, in which for two weeks I attended group therapy for five hours a day at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital in White Plains.

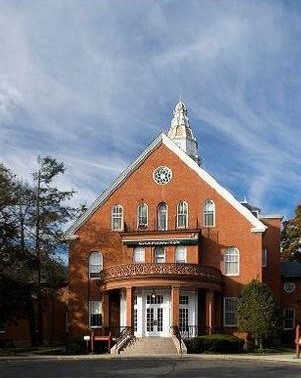

NewYork-Presbyterian

Hospital in White Plains, site of my partial

hospitalization in 2013

My memory was still scrambled from ECT, which apparently made me unfit to drive, so I had to take a bus there and back every day. This being Westchester where practically everyone has a car, the bus was sparsely populated—just a few shift workers, mostly Black or Hispanic, sharing the vehicle with a nut lately out of the nuthouse.

The partial hospitalization program specialized in DBT, the same therapeutic approach that had been used on Martha at Silver Hill. It was mostly psychobabble to me, as I think it had been to Martha, with lots of acronyms like DEAR MAN (I still can’t remember what it stands for). They emphasized mindfulness, the art of living in the present that oddly seemed to me like a relic of the past. I had learned about it years before when I underwent cognitive-behavioral therapy, or CBT, and years before that when I learned Zen meditation from a spiritual director in Seattle. Therapists seemed to put great stock in mindfulness, and it sometimes helped to calm me. But it never produced the great therapeutic effects they seemed to hope it would.

I was still sick with a lingering cold I had picked up in One South, and depressed and suicidal for at least part of the day most days. To fight the depression, I tried to train myself to look at Martha’s eighteen years as a gift. They were the best years of my life, but they had a time limit, and the limit was part of the gift. To accept the gift was to accept the limit. Because of that gift, I was the luckiest man on the face of the earth, just as I had written to myself in my note to myself in One South.

Thinking this way helped me to feel better. So did forgiving God for having let Martha die. The idea of doing that struck me one day in church when I said the Our Father, with its line, “Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.” God cannot objectively sin, and in that sense doesn’t need forgiveness. But he can trespass against me in the sense of thwarting my desires, and he had trespassed against me in that way by letting Martha die. So I forgave him. I also asked him to forgive Martha for her suicide, if he hadn’t already, and I forgave her too, if I hadn’t already.

One thing that didn’t much help at partial hospitalization was an irritating instructor named Janel, a beady old lady who closed her eyes a lot when she talked and was critical and domineering. Every time I had a group therapy session with her I left more depressed than when I started.

###

When the two weeks of partial hospitalization were over, I returned to work at MediStory. Having been away for eight weeks, I assumed everyone knew where I had been—that I had gone crazy and been locked up in an asylum. But the secret seemed to have been kept pretty well. My two bosses knew, and the editorial director, and the partners who owned the company, and that was it.

Since the owners and my bosses knew, I figured there was no point in keeping it secret from my fellow underlings, so I was open about it in a way I had never been about my bipolar disorder. In particular, I wanted Stevie to know. I considered myself mostly free of her spell, and I didn’t want to fall back into it. But we were friends, and I thought she might be interested in what goes on in a psychiatric ward.

On May 20, Stevie and I had drinks after work. We sat and talked together for hours, with me drinking more Scotches than I could count and Stevie drinking vodka and soda. Periodically, we stepped outside for her cigarette breaks; I didn’t smoke but we kept talking while she smoked. By the time it was over I was in love with her again. She was so gorgeous, sometimes with her long dark hair loose on her shoulders, sometimes caught up in a ponytail; sometimes she wore glasses, sometimes not. My memory was still messed up, and she refreshed it by telling me who the various MediStorians were and what was funny about them. We talked about the big wooden table in the MediStory kitchen, where Stevie often sat to chat with fellow employees at lunch while I avoided coming close. She encouraged me to join her there, and I said I would.

At the end of our drinks, I kissed her on the cheek, and I wanted to kiss her for real, on the lips.

The next day I joined Stevie and some others at the lunch table for the first time, making small talk with them as though it were normal for me to be there. Afterward Stevie emailed me, saying, “That wasn’t so bad.” I wrote back, “Because you were there.” She said, “Yay! I’ll be there :).”

And so I became a semiregular denizen of the lunch table, which Melinda liked to call the Algonquin Round Table for the type of scintillating talk that it lacked. I sat there not for the conversation but because it gave me more opportunities to see Stevie. I worked out an elaborate fantasy about Stevie, in which she invited me to see her apartment, one night when her live-in boyfriend wasn’t there. We started making out, then had sex, then it turned out she’d neglected to use birth control and was pregnant. We decided to marry, and she left her boyfriend and I divorced Melinda, and we raised our child together. It was a boy this time.

The child was the climax of the fantasy because ever since losing Martha that was what I most wanted from Stevie. Melinda and I were talking about adopting a child, and I made inquiries about it to friends who had adopted and to adoption agencies. But I never totally liked the idea of adoption because I would be nurturing someone else’s genes, not mine. With Stevie, at least in fantasy, I had the chance for progeny of my own.

Around the time I was thinking all this, my latest short story, “Lunch,” got published in Eureka Literary Magazine. My fourth published short story, it was about my obsession with Sarah, the lunchmate I had fantasized about before discovering Stevie. At that time, I was still meeting Sarah once in a while after work in a midtown hotel bar equidistant from our two places of work. I drank Scotch while she drank seltzer or club soda. I had never disclosed to her how attracted I was to her, but I wanted her to read my story, and it talked all about that. So I let her know about the story, and she wanted to read it. I warned her about the sexual aspect—I told her I had always found her beautiful and had been attracted to her, and let her know that was part of the story. She took this in good stride and still wanted to read it. So I gave it to her.

Our friendship never recovered. Sarah didn’t get back to me for days about “Lunch,” and when I finally called and asked her about it, she was mad. The story had offended her. I had portrayed her as crazier than she really was, she said. And she had been creeped out by my desire for her, which she didn’t reciprocate.

I should have expected this reaction. In fact, I had expected it. I had hesitated to show Sarah the story for fear that she would take offense and I would lose the friendship. But I had shown her the story away. I suppose I was still sweet on her, and I secretly hoped that learning about my desire for her might prompt her to say she felt the same way. In a way, it was another version of my writing a letter to Mary Ann telling her about my feelings for her. Mary Ann had forgiven me for that and remained my friend. But Sarah showed no such inclination.

When we talked on the phone about the story, Sarah and I agreed we could still be friends, but it was clear our friendship had been damaged. Indeed, a year passed before we saw each other again, and three years after that before the next reunion. Sarah had been one of the greatest comforts to me after Martha died, with her appearances at Martha’s wake and funeral and with our get-togethers since then. I credit her for her kindness then, and blame myself for the coldness that followed.

###

Fresh from the fiasco with Sarah, I was careful not to tell Stevie how I was fantasizing about her. But it may be she intuited it. For reasons she didn’t explain, she grew distant. It became harder for me to schedule a lunch with her; I’m not sure I ever did after our night of drinks.

Maybe I overburdened her. Stevie was young and effervescent, and I was an old man still in mourning over a dead child, slogging through depressive episodes that continued even after my hospitalization. I had nothing fun to talk about, just death and insanity. At our company picnic at the founder’s house in Connecticut, she saw me sitting alone at a table under an umbrella and walked up to me in exasperation, saying, “Why are you sitting here all alone?” I was sitting alone because I was miserable and had no friends, but I didn’t say that. She asked me to join her on the grass watching the young men play sports, but though this appealed to her it had no appeal to me. I joined her anyway and asked her to go for a walk with me. “It’s too hot,” she said. So I went for a walk by myself. Really, what could a girl like Stevie do with an aged malcontent like me?

I realized I had to break up with Stevie. This was difficult since we had never really gone out. But she was making me more unhappy every day. My psychiatrist, Dr. Sanders, was always ready to raise my medication as a solution to any problem, so he raised my dose of Geodon, an antipsychotic I was on at the time.

I’m making it sound like all I did in those days was mope about Stevie. But there were many things I moped about. I moped about Martha, replayed in my mind all the ways I could have saved her life had I been less selfish and lazy. I moped about work, which continued to be boring and stressful. In July, I went to Florida to help my father mope about his dead wife, on the one-year anniversary of her death on the eighth. We visited the niche where her ashes were stored, but I didn’t mope much about her death—I never had. Mainly I remembered that the last time I was there at the columbarium, Martha had been there too.

And I didn’t just mope. I revised my novel The Kids from Queens, the one I had finished in One South, with the imaginary sexual affair between me and a high school version of Martha. That summer I finished second and third drafts of the novel, and got closer to the point where I could seek publication for it. Maybe this would be my first published novel. I was excited to find out.

While I worked on it, the Stevie situation worsened. Years earlier, before I got married, I had been romantically entangled with a married woman and had learned that the real danger in extramarital affairs came not from the woman’s husband, who was obviously of little interest to her, but from other extramarital lovers. They were the ones to be jealous of; they were the threats. Sure enough, as my own appeal to Stevie faded, I noticed that she was spending more time with other men at work. One of them, a handsome young man named Karl, took her out to lunch, the way she and I used to go to lunch. Another day I spotted her sitting in the park with a middle-aged editor named Aaron, who unlike me had his own office and living children. More and more, the Algonquin Round Table was dominated by her conversations with Aaron, whom she seemed to find much wittier than I by the greater zeal with which she guffawed at his jokes.

I felt jealous, betrayed, ignored, hurt. I returned to my idea of jumping off the MediStory roof. Alternatively, I pictured inserting a carving knife into my heart. It might be difficult to find my heart, but if I did lots of exercise to pump it up, I would feel it pounding, open my shirt, circle it with a Sharpie marker, then plunge a knife into it.

Before I could do that, MediStory let me go. On August 20, the managing partner and the editorial director informed me that MediStory was having economic troubles and therefore had to lay me off. My last day would be September 13.

I couldn’t prove that MediStory laid me off because I was bipolar, but the timing was suspicious. For eight years, I had worked for them, earned stellar reviews, and survived waves of layoffs. This was the first year I disclosed to them I was bipolar and asked for a medical leave. Within about three months from when my medical leave ended, they let me go. They left just enough of a gap in between so they could claim the two events weren’t connected. I thought of filing a discrimination suit against them, but didn’t have the energy. And anyway you could as well say they laid me off because I’d lost a child. It was the death of Martha that had driven me into the mental hospital, and the mental hospital that had driven them to let me go. There’s no law against firing people who had the poor cosmic taste to have a child die.

At almost the same time, Stevie announced she was leaving, but in her case it was because she had found a better job. Her leaving was a victory, mine a defeat. When I learned about this, I tried especially hard to get together with her one last time, for drinks or lunch, but she said she was too busy. I asked for her contact information so I could reach her after she left, but she said she was too busy to give me that either. I went to see her in her cubicle, where I almost never appeared, and asked, “Is there some reason you don’t want me to have your contact info?”

She pointed to how busy her computer screen looked. “No, I’m just busy.”

And I knew she was cutting me off. She had had enough of me and my grim, death-centered, bipolar life. Eventually, she sent her personal email address to the whole company, including me, but I knew better than ever to contact her at that. She would have given me her phone number if she had ever wanted me to call her.

Right before she left, Karl, one of her paramours at work, threw her a party at a local bar. I didn’t go, because I couldn’t bear to compete with all the other men who would be there vying for her favors. I would always be grateful to Stevie for having been kind enough to go to Martha’s wake. But I could see our relationship would serve no further purpose, and I never tried to get together with her again.

Copyright 2020 George Ochoa.

Write a comment